Should I Trust Myself to Invest My Own Money?

Introduction

Let’s face it: money is a touchy subject, so much so that many of us miss out on major opportunities as a result of avoiding taking it head-on out of discomfort and lack of understanding. Money brings up uncomfortable feelings sometimes because of social class tensions and ‘keeping up with the Joneses’, shame for being or growing up in a low socioeconomic class, and middle- and upper-class professionals often feel confused and inadequate in managing their own money. Ultra high-net worth individuals also struggle, believe it or not, with aspects of their own wealth.

Regardless of where you started or where you are now, you have the ability to improve your future wealth, and it’s probably easier than you think. The phrase “if you don’t stand for something you’ll fall for anything” is often used in political discussions, but applies perfectly to investing. Without a clear framework for what you wish to accomplish with investing you cannot make decisions about what you should and should not do (more about this later). Similarly, if you don’t have a framework for choosing the right financial advisor for yourself you might end up not having your unique needs met (see Part 2 of this series).

For those entrusting others with their hard-earned money, a significant decision on its own, there are ways to make sure that your best interests are being served. If you’re managing it yourself, you’re not alone and there are helpful tools and technologies now that, more than ever, can help you grow your wealth.

Whether you’re saving for retirement, working towards a specific financial goal, building generational wealth, or managing a windfall, selecting the right approach to growing your wealth is crucial to achieving your financial goals. Regardless of which option you choose, be aware that having a clear purpose going into it provides meaningful guidance at the moment you need it most.

Let’s navigate the landscape of research on individual investing and professional wealth managers so we know the pros and cons of each. Then make an informed decision at each stage of your life. The critical detail is generally to first identify the incentives for each option. When the incentives aren’t clear, look even more carefully so you understand the nature of the engagement.

It’s worth noting and emphasizing that this article and associated seminar given by Prof of Wall Street is not nor should be construed as financial advice. Each individual person is unique as is their circumstances and future financial state so it is critical for you, the reader, to consider this in light of your own situation and consult with whomever you believe will provide you the best outcome as you define it.

How many people invest on their own?

About half of Americans do not have any money invested in the stock market (L. Guiso and Sodini 2012), although participation increases as wealth increases (Vissing-Jorgensen 2003). In other words, those who would benefit most from growing their wealth generally do not invest at all.

Some people choose to make their own investment choices by opening a brokerage account that allows them to choose what to buy and sell. The advantages of managing your own money are discussed at length below and include avoiding management fees from advisors (discussed in another article we highly recommend), learning over time how to be an effective investor, and possibly earning higher returns if you have a good investment process.

This first section is specifically for people who have savings and choose not to invest it, instead keeping it in a savings or checking account, or literally under the mattress. The rest of the article afterwards is dedicated to the reality of being a self-directed investor and what resources are available.

Storing Cash “Under the Mattress”

This is a common choice for many–hold onto my money and instead of investing it, put it under the mattress or in a bank. Today, few people keep physical currency stashed away in their homes as they did in the past, but some still do, but the interest rate is roughly similar when compared to investment alternatives.

Regardless of whether your savings are a hard lump under your bed or sitting in a savings or checking account, chances are that you are not earning meaningful interest on it or able to generate investment returns from it. If you already invest in one form or another, feel free to skip this section; if you have a friend, family member or colleague who shrinks from investing, share this with them.

People who hold large cash reserves often do so out of fear of investing—whether due to a past bad experience, fear, intimidation a lack of knowledge, or general market skepticism.

Even people who may, in principle, want to invest often miss out because of the following factors:

- Limited Attention: There’s too much going on to dedicate the time and effort to investing. We ran a study on pension fund participation a while back and discovered that despite attractive opportunities to invest and receive generous matching funds, many people were too overwhelmed to pay attention to the offer sent. From a rational perspective it makes no sense, but nearly everyone can relate to being too busy to attend to great opportunities.

- Distrust: Many people have a distrust of financial markets, specific companies, and/or sovereign governments. In the study mentioned above we found trust being a meaningful factor that kept people from wanting to invest their money in the stock market. This finding accords with a famous paper in finance (Luigi Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales 2008).

- Complexity Aversion: This relatively unknown but self-explanatory bias is one of the most useful for understanding why people don’t do something complicated. As it sounds, when people are confronted with something that exceeds their capacity to readily comprehend they shy away from it as they could make an error (Carvalho and Silverman 2024).

- Analysis paralysis: endlessly waiting for the “perfect” time to invest, while missing out on long-term gains. This is sometimes referred to as “time in the market” versus “timing the market” where the latter approach leads to gains over extended periods relative to even well-timed entry into a robust market such as the US equities market.

- Loss aversion: People dislike losing in general, but in terms of investing people fear short-term market drops more than valuing long-term gains; checking on market prices changes makes people focused on the very short term and is called myopic loss aversion (Gneezy and Potters 1997).

- Recency bias: overweighting recent downturns and underestimating recovery potential leads people to stay out. The market reliably has downturns and reflects the unpredictability of local states, country and global, interconnected geopolitics. When the market is down, people shy away from investing.

Let’s explore some of benefits and costs of holding cash:

Positives of Holding Cash

Psychological safety: What you get by keeping your money uninvested and at your immediate control (known as “highly liquid”) is a sense of control and predictability. Regardless of how much wealth someone has, each person has their own unique practical and subjective needs for safety. This varies greatly for people, but it’s worth going through the exercise of knowing how much money is needed in the event of loss of income stream (known as the “rainy day fund”). While the impulse to have a large store of cash is understandable, the amount of money stored can be far too much.

Happiness: Some research suggests that holding cash brings greater happiness than income (Ruberton, Gladstone, and Lyubomirsky 2016). This largely comes from a foundational need for safety (in the Maslow sense), and in today’s world cash effectively cushions people from feeling vulnerable and allows them to function more confidently, even seeking to meet higher-order needs such as happiness, fulfillment, and (gasp!) self-actualization.

Flexibility and Optionality: A big upside of holding significant cash is the “optionality” of that money, especially during a crisis. If you need the money immediately, you can access it and know exactly how much you have and how to get it. For people who did not invest in the stock market prior to a crash, they preserve the option of buying significantly undervalued assets and experiencing high, post-crash returns–”buying the dip” on the S&P index has always paid off handsomely at every crisis.

Negatives of Holding Cash

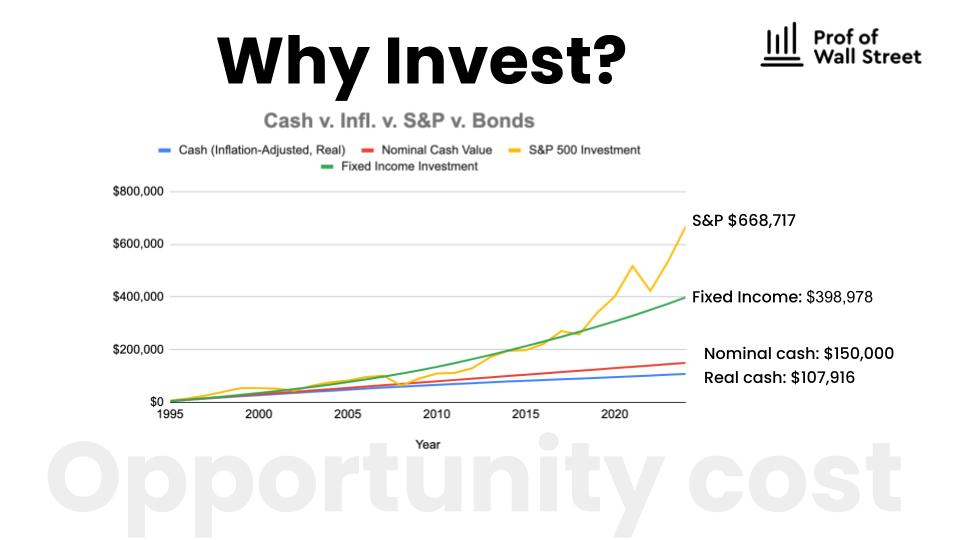

Opportunity cost: you lose the opportunity to increase your wealth through investments. By “sitting out” of the market, non-investors do not benefit from wealth-increasing opportunities of public markets. If you had $5,000 each year from 1994 to 2024 and you saved it in cash it would be worth $150,000 in nominal terms but only $107,916 in real terms, in purchasing power; the decrease is due to inflation ‘eating away’ at the purchasing power of the US dollar (average inflation over the period was 3.56%). Conversely, putting that same $5,000 per year into the US stock market in the Standard and Poor index of the largest 500 companies by market capitalization (the “S&P”), which grew an average of 9.7% per year would be worth $668,717.

The critical factor that humans drastically misestimate is compounding. This underappreciated force of nature that takes money and grows it over time by a percent not only increases the amount of money by that percent, but the amount itself that increased also grows. It’s this second portion that most people fail to compute intuitively, which is called exponential growth bias by behavioral economists.

Fear of Missing Out (FOMO): People sitting on the sidelines are likely to experience relief from what other investors are experiencing. Then, as the market keeps going up people might continue to sit it out because of inaction inertia (the prize seems smaller and smaller over time). Then, ironically, people just can’t take it anymore and buy stocks, often at the top of the market and experience the painful downslide after peak price reached (and the bubble bursts, if there was one).

Inflation Losses: To estimate the missed opportunity of not investing is to add the percent of monetary inflation to the returns of “the market” (which is typically represented as the performance of the Standard and Poors index of the 500 largest US companies).

But it’s not the price increase, there are dividends from stocks that can provide cash flow and buy more shares at discounted prices in dividend reinvestment programs (DRIPs). There is also missed rental income from real estate.

Personal growth: Another, non-obvious downside of not participating in the stock market is the loss of opportunity of learning about yourself as you go through your own investment journey. At Prof of Wall Street we recommend learning how to invest before investing any meaningful amounts of money through our “paper training” program. By participating with real money or training, you gain an understanding of how markets behave in different conditions, develop emotional resilience to market fluctuations, and learn how your own biases (it’s ok, we all have them), such as loss aversion or overconfidence, affect decision-making.

If, despite the opportunity cost of investment you still wish to keep all of your money as cash, at least consider getting the highest interest rates possible. We found a US-based firm specializing in finding the maximum interest available on cash across US banks called “Max My Interest” and we would suggest considering this as an option to increase your interest yield while preserving the liquidity of your cash.

For those who wish to invest on their own as self-directed investors, the following section is dedicated to the endeavor.

Reality of Self-Directed Investing

Investing one’s own money is a noble challenge that many people shy away from. Many people feel like they don’t have enough money to even begin investing, don’t know the first step to opening a brokerage account, and feel uneasy about putting their hard-earned money at risk despite all the compelling marketing and social messaging now at an all-time high.

Some of the hesitation is warranted, as most retail investors don’t consider that they are effectively running their own fund. They generally think they’re just self-directed investors ‘doing their own thing’, but in reality they are running money for their family and often without the necessary structure, rules, or governance that keeps portfolios serving their purpose over long periods of time. And almost no self-directed investor has an investment policy statement (IPS).

The odds aren’t good for retail investors.

For those investors who are adept at selecting future high-performing assets and managing them through the inevitable ups and downs, stand to gain more than people cannot do both of those well. Yet evidence suggests that self-directed investors generally lose significant sums due to overtrading (Odean 1999), overconfidence (Barber and Odean 2000), gamble and select lottery-type assets (Dorn, Dorn, and Sengmueller 2015), trade for fun over profits (Grinblatt and Keloharju 2009), and, in aggregate, lose money (Odean 1998). Overall, only about 90% of do-it-yourself-investors are successful and overall short-term traders lose money (Barber et al. 2023).

However this doesn’t have to be the case for you as a retail investor.

Prof of Wall Street provides behavioral financial technology and resources to build a clear investment policy to help you separate yourself from the mass of losing investors and build long-term wealth for you and your family. Feel free to download the Prof of Wall Street Guide to Investment Policy Statements here. An IPS helps you with the big decisions up front so that when turbulence hits you have a game plan, plus the technology to help you succeed over the long haul of wealth building.

If you are already a self-directed investor, Prof of Wall Street behavioral technology is designed to help you be your best. We developed world-first behavioral technology that finds upside in your portfolio by analyzing your historical trades, plus guides you to better future investment decisions with our investing tool.

Let’s break down the pros and cons and see which resonate with you:

Positives of Being a Self-Directed Investor

Lower Costs: Per-trade costs have decreased drastically and are now zero across many platforms. Do not mistake per-trade cost as the total costs of investing, as you can pay more than you expect when there is a large bid-ask spread, you pay fees when you borrow money in margin accounts, and miss out on opportunities to earn interest on your uninvested cash.

Wider investment options: As a self-directed investor you are able to invest in a wide range of assets (although more choices isn’t always better and some choices should not be considered “investments”, but that’s another topic).

Growing Wealth Beyond Work Earnings: This is probably the primary motive for most investors–to get richer faster than they would by working and saving alone. If you invest wisely and consistently do the right things (which sometimes is doing “nothing”), then long-term investors can meaningfully grow wealth.

Unconstrained decision ability: Unlike professional managers who have strict limits on their decisions, you can essentially do whatever you want in terms of buying and selling assets. Because of this freedom, we at Prof of Wall Street highly recommend drafting your own investment policy statement to help you make educated decisions. The Chartered Financial Analyst board publishes a useful guide (available here for free) that you can use to draft a set of rules to guide your decision making.

Reaping the benefits of your own work: There is pride in taking on a challenge, and successful investors gain pride from seeing their wealth grow above and beyond what they started with. There is risk, of course, but wise investors can reap the benefits of their investment acumen and save money to change the trajectory of their lives, and even help others do the same.

Personal development: Self-directed investing requires a journey of self-discovery. As you face uncomfortable situations, pain and euphoria, you’re not just growing your wealth – you’re growing as a person. Each decision you make, every market swings you weather, sharpens your analytical skills and builds your confidence and experience. You start to see the world differently, noticing economic trends in your daily life and understanding how global events ripple through markets. It’s a crash course in critical thinking that spills over into other areas of your life.

But it’s not all about numbers and charts. Self-directed investing teaches you patience, discipline, and emotional control. You learn when to trust your judgment while staying humble enough to admit when you’re wrong. The process of setting financial goals and working towards them cultivates a sense of purpose and long-term thinking, which for most people is difficult. And there’s something incredibly empowering about taking control of your financial future.

Negatives of Being a Self-Directed Investor

Risks of Losses and Lower Returns: Self-directed investors face significant risks of losses and potentially lower returns (this scary pattern is mentioned earlier on, is worth repeating). This is probably not shocking to anyone, as one would expect normal people to struggle at least initially with complex decision making. There are many reasons why people have low returns and large losses, and they include frequent trading (Odean 1998) and a complex interplay of behavioral biases, which not only increases transaction costs but also typically results in underperformance compared to a disciplined, long-term investment strategy.

Statistics suggest that less than 10% of self-directed investors are profitable, highlighting the challenges of consistently generating positive returns without professional guidance. We mention this a few times so pardon the repetitiveness, but solve this problem at Prof of Wall Street with our guided investment tool and invite you to use it.

Behavioral Biases in Asset Selection: There are a number of serious biases investors display in choosing what to invest in. One of them is called “lottery preferences”, whereby investors choose low-priced stocks because they believe that they are “cheap” and have large upsides (Kumar 2009). This common behavior is understandable, yet when an investor considers that the majority of these investments are in companies that are “early stage” and unlikely to survive, much less beat any relevant benchmark, they become, hopefully less attractive and are seen and allocated to as the speculations that they are.

Unconstrained decision ability: You’re not seeing double, this is also one of the biggest benefits. The research on self-directed (“retail”) investors shows the unsurprising outcome of what happens to people with no training or help investing on their own. The disappointing results should be no more surprising than seeing someone who has no training or help try to surf on their own and fail to catch any waves and possibly drown trying.

Given that self-directed investors are unconstrained, this freedom comes with meaningful responsibility to know what they are doing. Most people resort to books, online resources, and so-called experts from various media types. But how can we know who to trust with guiding your decisions?

Time Commitment: Some investors dedicate substantial time to researching investment opportunities, analyzing market trends, macroeconomics, and understanding financial instruments (e.g., using options to reduce downside risks). Regularly monitoring and rebalancing a portfolio to align with financial goals requires ongoing effort, unlike passive strategies or professional management, which demand less active involvement. Building the knowledge and behavioral and cognitive mastery needed to make informed decisions can be time-intensive, especially for beginners.

The time spent on self-directed investing also leads to an associated opportunity cost (the potential gains of time spent elsewhere foregone). For instance, a DIY investor might allocate time to actively manage their account instead of, say, working on growing their business, career advancement, pursuing hobbies, or spending time with family.

Knowledge Requirement: This includes a strong foundation in financial concepts such as understanding various investment vehicles like stocks, bonds, ETFs, and mutual funds, as well as grasping fundamental economic principles. Investors must also be familiar with risk assessment, diversification strategies, and portfolio management techniques. Additionally, they need to be skilled in market analysis, able to research and interpret financial statements, understand market reports, and stay informed about global economic events that could impact investments.

Beyond technical knowledge, self-directed investing demands strong emotional control and discipline. Our behavioral algorithms are designed to detect and correct behavioral patterns in order to unlock performance potential in a customized way. In general, investors need to make rational, fact-based decisions without being swayed by market hype or personal biases and capitalize on opportunities when others are influenced.

Stress: When the stock market does poorly it hurts more than just people’s account balances–some people have heart attacks (Engelberg and Parsons 2016) and there is evidence that strokes and other serious cardiac events occur due to financial market volatility. Even if it doesn’t kill you, being exposed to a force that you cannot control or reliably predict is stressful for most people. Unfortunately, financial losses do lead to death, with the most striking and horrific case being the suicide of a college student in June of 2020. But besides this sad and well-publicized example, many people suffer from both trading and gambling losses with dire consequences on personal relationships, family stability, and long-term wealth trajectory.

Investment Platform Incentive (misalignment): In an article titled “Nudging to Trade” on Medium, our founder, Dr. Amos Nadler, discusses how investment platforms seek to satisfy the objectives of the platforms over those of the retail investor. We at Prof of Wall Street believe that incentives should be aligned between client and provider and built de-biasing software to help investors make better decisions and grow their wealth. This is a non-obvious aspect of self-directed investing but early research on the use of internet sites to make investment decisions suggests that people do worse–sometimes much worse–when investing online (Barber and Odean 2001).

If we as Do-It-Yourself (DIY) investors need to make our own decisions, where do we get our investment ideas and financial information?

Self-Directed Investor Resources

The following are some of the resources self-directed investors have at their disposal to make their own investment decisions:

Using academic research to guide investment decisions presents both challenges and benefits. On the one hand, academic research offers rigorously tested theories and data-driven results that can improve understanding and, sometimes, be extended for investment and behavioral decision-making. Procedurally, research-based approaches can reduce reliance on intuition or external biases, enabling investors to make more informed, data-driven decisions. This foundation of evidence-based analysis is particularly valuable for long-term investment strategies, where accuracy in business valuation and risk assessment is critical.

Another under-appreciated aspect of academic research is the rich, descriptive language it generates that allows us to understand concepts that are essentially invisible to practitioners and laypeople. For example, knowing the phrase “efficient markets” helps focus the discussion on whether current prices are accurate or whether a meaningful opportunity exists.

However, there are notable limitations. Much of the finance literature has been criticized for its insularity and limited real-world applicability, with a focus on abstract models that may not address practical investment challenges. Moreover, financial conflicts of interest (and even outright forging of results–gasp!) can sometimes influence research outcomes, leading to potential biases in study design or interpretation. The slow pace of academic publication also means that research often lags behind rapidly evolving financial markets, making it less responsive to immediate investment needs.

Overall, while academic research can provide valuable frameworks and insights, investors must critically evaluate its relevance and complement it with practical protocols to execute effective decision-making.

Many retail investors still turn to newspapers and magazines as a trusted source of information. These traditional media outlets are seen as credible and trustworthy as publications like The Wall Street Journal, The Economist, Barron’s, and Financial Times are known for their rigorous editorial oversight and fact-checking and tend to lean more conservative relative to other outlets covering some of the same topics. Whether you’re interested in stocks, mutual funds, or broader economic developments, these publications provide a comprehensive view that helps you understand the big picture.

However, there are some limitations to relying solely on newspapers and magazines. For one, they can’t keep up with the speed of digital media when it comes to real-time updates (although digital versions have live data feeds and they update stories in near-real time). Additionally, the print media industry is facing challenges, with declining circulation and rising costs. Some publications might also have biases due to advertising revenue or corporate relationships, which can influence their reporting. And while journalists do their best, they might not always have the financial expertise to dive deep into complex investment scenarios.

Investing books provide foundational knowledge and engaging ‘war stories’ but may not address current market conditions or promote unbiased strategies. One of the more engaging and transparent books about actual people and their unique approach to trading is the Market Wizards series by Jack Schwagger (but good luck replicating their performance). There is meaningful disagreement between popular authors and finance professors (Choi 2022).

Stock analysts, whose opinions are available on various investing sites as well as through investing platforms offer detailed research and recommendations, though conflicts of interest, biases, and high costs can limit their reliability (Lim 2001). Perhaps helpful is that each analyst receives a simple star rating so that the weight of their analysis can be estimated by their historical accuracy.

Investment platforms not only allow investors to place their own orders directly but they aggregate news, analyst reports, and other relevant information so that decisions are informed by available information. The downside of investment platforms is that the incentive to facilitate good decisions is not sufficiently strong relative to inducing trades, as many investors fail to achieve positive performance and stop investing altogether (Godina et al. 2020). Prof of Wall Street provides a robust investment process that debiases investors and leads to better returns in order to help investors not only survive, but thrive despite the challenges.

Financial influencers make investing approachable, especially for younger audiences, but their advice varies in quality and may prioritize monetization over accuracy. Early influencers like Suze Orman and Dave Ramsey have historically helped improve financial literacy and savings rates among their audiences (Chopra 2021). Also, the advice often takes into account the real-world challenges people have in sticking with a financial or investing plan (Choi 2022). In an important step towards providing ‘quality control’ over content, a recent German study evaluated finfluencers (Zülch et al. 2024) and provided a “FinQ” score. Do we consider ourselves influencers? Not sure, but you’re welcome to follow us on Youtube, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

Investment newsletters offer both advantages and drawbacks. On the positive side, they can provide investment ideas, and potentially identify opportunities they might otherwise miss. However, these publications also come with significant risks. The quality of advice varies and some newsletters may have conflicts of interest or promote biased information; performance of Hulbert Financial Digest newsletters, overall, was found to not outperform appropriate benchmarks (Jaffe and Mahoney 1999). There’s also a danger of investors blindly following recommendations without conducting their own due diligence and acting without considering whether the recommendations comply with their own risk tolerance and/or investment policy statement. Additionally, the cost of subscriptions can eat into investment returns, especially if investors feel obligated to act on recommendations to justify the expense. While investment newsletters can be useful tools, it’s crucial for investors to approach them critically, use them as part of a broader research strategy, and always consider their own financial goals and risk tolerance before acting on any advice.

Social media platforms like Reddit, X/Twitter and Stocktwits provide diverse perspectives but risk misinformation and herd mentality. This is a highly controversial area with high stakes.

This list would be critically incomplete without Artificial Intelligence (AI). This factor is dramatically changing all the parameters about what you read above and changing the industry so quickly that this article is likely to require regular and massive rewriting to stay current. AI touches on all of this: From being able to summarize entire literatures (this can take humans months to do, we know, we’ve been through it), to writing and deploying code to pull market data via API and run near-instant analysis correctly, to writing software that can trade on its own.

The final, critical category is also the newest–behavioral financial technology (behvioral fintech). This is the necessary evolution of investment technology that brings together the best of research, decision support, real-time data, and Nobel Prize-winning behavioral economics. Pioneered by Prof of Wall Street, behavioral fintech allows investors to identify their investment upside by analyzing their historical data, and benefit from a robust investment guidance tool. Click here to read more about behavioral fintech, get your account today, or reach out to schedule a one-on-one with a Prof of Wall Street team member.

Overall, each resource has its strengths and weaknesses, requiring investors to critically evaluate and tailor them to their needs. There have never been more options for retail investors, which probably make investing more difficult because of the added layer of sorting through the various inputs to identify the reliability and quality. Ultimately, each person chooses a mix of resources that fits their preferences, budget, and abilities.

Along with the pros and cons of each input, always consider the incentives of each source when purchasing and/or using it to make decisions about your own money.

Conclusion

There are investors who are able to meaningfully grow their wealth through self-directed investing. Historically, they were largely already high net worth individuals who benefited from social support, high financial literacy at baseline, higher income and subsequently greater risk capacity, and other benefits. We believe that many of the toughest challenges of investing can be improved by technology, rather than made worse–if and only if the incentives are in the right direction.

If you are an investor and want to learn what upside you have in your portfolio, and how you can increase your wealth through better decisions then reach out directly right away to us. We have the experience and analytics to surface critical insights that will provide actionable ways you can earn more as an investor.

If you’re interested in learning whether you should trust professionals with your money, explore our article here.

Citations

Choi, James J. 2022. “Popular Personal Financial Advice versus the Professors.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4203061.

Chopra, Felix. 2021. “Media Persuasion and Consumption: Evidence from the Dave Ramsey Show.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3992358.

Guiso, L., and Paolo Sodini. 2012. “Household Finance: An Emerging Field.” Microeconomics: Intertemporal Consumer Choice & Savings eJournal, April. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-44-459406-8.00021-4.

Kumar, Alok. 2009. “Who Gambles in the Stock Market?” The Journal of Finance 64 (4): 1889–1933.

———. 1999. “Do Investors Trade Too Much?” American Economic Review 89 (5): 1279–98.

Zülch, Henning, Marius Mölders, Jannik Fennen, Julian Mathes, and Christian Pieter Hoffmann. 2024. “Finfluencing Charlatans Beware: Introducing the Finfluencer Quality Score (FinQ-Score) to Foster Trustworthiness and (business) Partnerships.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4800441.